19 September 2022 (reference to nineteenth century Irish speaking)

12 September 2020 (Eighteenth century Wicklow, see below)

10 January 2017 (the sounds of Wicklow Irish, see below)

The Irish of Co. Wicklow

Until a very recent date, some in the county spoke Irish, but the mines of Tigroney, near Avoca, and the Glendalough mines caused a strong immigration from surrounding counties, and it must be remembered that districts such as North Kilkenny, North Wexford, South Dublin, and quite near, were intensely Irish-speaking [sic!] at O'Donovan's time [i.e. the Ordnance Survey Letters], a century ago. This creates the absolute need of verification of the origin of every old man or woman in Wicklow claiming to have known Irish, dating 1830, 1848, etc. (p. 10)

Like most of

Ireland, Wicklow was predominantly monolingually Irish for centuries. That

Wicklow was the first county to lose its Irish almost entirely – apparently

during the eighteenth century – should not obscure the fact that this process

happened gradually in Wicklow, just as it did everywhere else in Ireland. The demographic

retreat of the Irish language in Wicklow – as in every other county – would

have resembled a receding tide, with stranded remnants of Irish-speaking communities

in remote and mountainous areas before they too, in time, ultimately succumbed to English as well.

In this context, it is illuminating to consider a description of Wicklow sketched in the curious piece The Pretender’s Exercise (1727), quoted in Bliss' highly recommended Spoken English in Ireland 1600-1740 (1979: 159-161). The Pretender's Exercise is a Trinity College-produced propaganda piece which portrays Irish-speaking conscripts in the Jacobite Army abroad being drilled in pidgin English by an officer who is clearly meant to be a native speaker of Irish just like them. One recuit is from Glenmalure, and this conscript’s dialogue with the officer is based upon criticism of the conscript’s poor English (the butt of the joke apparently being that the officer’s English is just as bad).

Question. Fat Name upon you dere?

Answer. My Name Byrn.

Quest. Fer vash yo[u] Born?

Ans. County of Killamountains.

[Quest.] De Tivil take you, can’t you call him Countys of Wicklows? I make English upon you, you make English upon me again, and be hang’d you Tief. Fere dere?

Ans. Glanmalora. It ish a good Plashe, a bad Name, all von for dat.

Quest. Fat Relishion?

Ans. A Roman Catalick.

[Sergeant.] Very vell. To de Right, put in your Toe, put out your Heel, shit ub strait!

Nevertheless, isolated speakers (or in some cases semi-speakers) could still be found in Wicklow well into the nineteenth century. Piatt (1933: 6) reports that ‘Andrew and Hanna Byrne of Glenealy, who both died in 1830, are the last absolutely authentic native speakers I can find in that area’ and claims the grandmother of a Mr John Byrne of Cloneen ‘dead about the Famine period, knew Irish’ (ibid, p. 2) – probably a semi-speaker. A grandson of Irish-speaking Connacht immigrants to Glenmalure told Piatt that Irish was still spoken in that area when his father, who died in 1884, was a boy, i.e. around 1810.

Nevertheless, the available evidence strongly suggests that Irish survived longest and strongest in a broad area west of Avoca, as that is where most mentions of Irish survivals and last speakers (and semi-speakers) in Wicklow cluster.

In the north of Wicklow, the last place where Irish was spoken natively may have been Glencree, directly adjacent to the last Irish-speaking area of South Co. Dublin, Glenasmole. Piatt (1933: 6) reports that around 1900 ‘people in the hills near Glencree knowing a little Irish, prayers, snatches of songs, etc., but not fluent’ implying a situation remarkably like that of Derrybawn in 1875. We may therefore assume a similar four-generation time span and that Irish had died out around Glencree circa 1820 at the latest.

Glenmalure, Co. Wicklow (Wikimedia Commons)

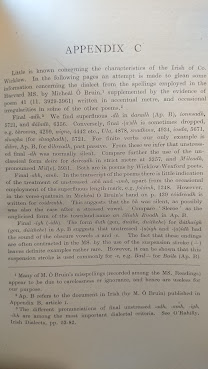

Nevertheless, we can from a number of sources identify some general yet key features of the Irish dialect(s) of Co. Wicklow. A great many of these come to light through spelling mistakes in texts in Irish written in Wicklow whilst Irish was still the spoken language of the area, which reveal the pronunciation of the writer (primarily the Leabhar Branach or Book of the O'Byrnes, a book of poems composed in Glenmalure between c. 1550 and 1630); secondly, other idiosyncrasies of local pronunciation have been preserved in place-names (the place-names of Wicklow were painstakingly studied by the late Dr. Liam Price until his death in 1967); lastly, we can infer a great deal about the dialect(s) in question from the few Irish words that have survived in the Hiberno-English of Wicklow, primarily collated by the late Diarmuid Ó Muirithe.

The sounds of Wicklow Irish

-adh, -amh and -abh

As in South Dublin and Offaly (at the very least), the endings -adh, -amh and -abh in e.g. déanamh 'do', talamh 'land' etc. were invariably pronounced the same throughout Wicklow, namely as -a (i.e. most likely as a schwa sound like the -a in Eng. sofa). This is perhaps the most quintessentially Leinster feature of the Wicklow dialect (and of the dialects of South Dublin and Offaly, and probably Kildare too); the rule elsewhere in Ireland is to differentiate between -adh, -amh and -abh. Very generally, north of this area these are pronounced -ú (as in Ulster, although this feature was the norm at least as far south as Athlone, Longford Town and South Meath), and southeast of it -amh is pronounced -av, -adh (in nouns) as -a, and -adh (in the past tense) as -ag (as in Ossory and Munster). The Leinster dialect, of which the Wicklow dialect was a central member, was thus particularly distinct in this regard.

-igh, -aigh

As in the rest of Old Leinster, -igh was probably pronounced -e and -aigh was probably pronounced -a in Wicklow. I strongly suspect that in Wicklow (as in Dublin as far as I can tell) these two sounds had in fact fallen even further together as a schwa sound i.e. [ə] identical to -a above. This leads to the extraordinary situation of -adh, -amh, -abh, -igh and -aigh all having been pronounced as a neutral vowel (i.e. as -a in Eng. sofa) in Old Leinster (including Wicklow). How this may have affected comprehension I cannot say.

-cn, gn

Three-quarters of Ireland habitually pronounce(d) initial cn- and gn- in words such cnoc 'hill' and gnóthach 'busy' as if cr- and gr- respectively; this change took place in the Middle Ages (Williams dates it to before the thirteenth century). Almost everywhere north of a line from Clare (where both forms were used) to South Kilkenny, cr- was (and continues to be) the norm; south of this line, i.e. in parts of Clare, West Kilkenny and all of Munster, cn- and gn- remained cn-. Wicklow was no exception to this rule and throughout the region cn- and gn- were nearly always cr- and gr-, disagreeing with Munster but agreeing with all other dialects.

ao

This spelling, in e.g. gaoth 'wind', is generally pronounced either [i:] i.e. í in Connacht, [ɯ] i.e. a close back unrounded vowel in parts of Donegal (and historically throughout most of Ulster and Louth), or as [e:] i.e. é in Munster and Ossory. In Wicklow (and South Dublin) ao was probably pronounced [e:] i.e. é with Wicklow (and Old Leinster) disagreeing with Connacht and Ulster but agreeing with Munster in this regard, e.g gaoth > gaéh.

-ch, -cht

Neilson (1808), in his introductory grammar on Irish, claimed that 'ch, before t, is quite silent in all the country along the sea coast, from Derry to Waterford' - presumably thereby including the coast of Wicklow. O'Rahilly, in his masterpiece Irish Dialects Past and Present (1932: 112) also states that -ch was silent in (presumably the coastal part of) Wicklow right up to the eighteenth century. There is, however, no conclusive evidence of this that I have seen; on the contrary, there is persuasive evidence that in Wicklow both -ch and -cht were fully pronounced in all positions, as they were in all of the country outside Ulster and Louth. The question is more one of whether -th was pronounced as -ch, as in parts of Wexford and Ossory.

-bh-, -mh-

In the Leabhar Branach medial -bh- and -mh- are typically deleted and the preceding vowel lengthened, so that e.g. leabhar 'book' > leár. In so doing Wicklow concurs with Ossory and Munster and disagrees with Connacht and Ulster.

cad

We can confidently assign Wicklow in its entirety to the zone that used g- interrogatives (i.e. goid~gad < cad), as Labhrann Laighnigh (p. 170) records the mixed form Goidé an chaoi athá tú from Carlow, to the south east of Wicklow. Wicklow was thus surrounded to its west and north (Dublin also used goid and gad; see Labhrann Laighnigh p. 26-27) by g-forms and it is thus highly likely that Wicklow used them too, meaning the isogloss ran fairly cleanly from Tobercurry, Sligo (LASID pt. 61) to the Barrow. North Kilkenny (LASID pt. 6) also has goidé.

Detailed information about Wicklow Irish from the Leabhar Branach

Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1944.